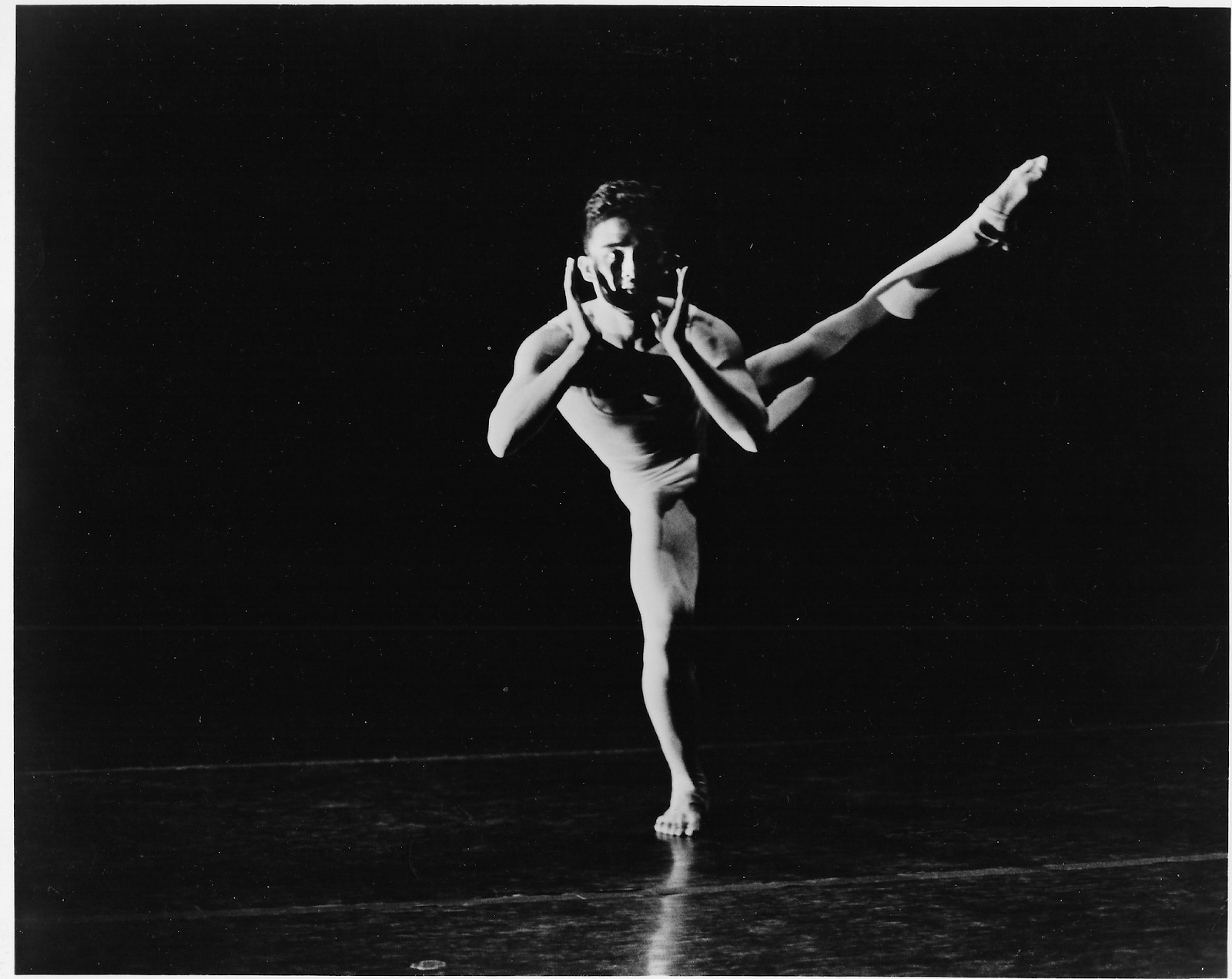

Passage. 1978.

Costume Design: Kwok Yee Tai

What Jenny Huang has written on Eleanor Yung and her choreography is beautiful. So well understood and articulated, I feel as if she were there, seeing Eleanor’s dance with us for the first time. Her writing makes explicit an embodied insight into being Asian American in the 70s when a racial/political consciousness was emerging. At that time the thumbs up accolades of mainstream dance reviews seemed enough, but they were certainly not writing for an Asian American audience. Jenny's critical perceptions of that - an analysis of how we are perceived - is most helpful. It is a remarkable moment to have Jenny Huang do this now some thirty years later. It is our pleasure to share this piece with you.

After introductory remarks on the term ‘Asian American’, background on Eleanor starts on p2, Basement Workshop on p3, Eleanor’s comments about Asian American dance and the make up of the company on p4, the Ribbon Dance and Passage on p5, Kampuchia p6, the developing purpose of the traditional company p7, Asian bodies, Orientalism and mainstream reviews p8, p9, & p10.

Eleanor Yung’s dance ‘Passage’, accompanied by Korean shamanistic music, reflects the transformation during the life's journey one takes. The costume designed by Kwok Yee Tai, also evolves like a ritual as the dance progresses. Unfortunately there were no color images of the dance extant and Kwok Yee Tai’s design, except for this color mock up which had been misplaced for decades. It was fortunately re-discovered recently and can be posted here to complement Jenny’s article. The public can now see the original costume, imagine with each stage of the dancers procession, it dissolves layer by layer till finally the dancers conclude the performance in neutral tone only. A video of Passage can be seen at the Lincoln Center Performing Arts Library. Reviews of it can accessed at http://artspiral.org/statement.php and http://artspiral.org/artisticdirector.php

- Research paper shared courtesy of author, Jenny Huang

- The full research paper can be found here:

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1_irjMdM4QPgzdWhCxwYFN6a2pJvDuzNhuBdlEiiPi8Y/edit?usp=sharing

- Information regarding the Asian American Dance Theatre (AADT) can be found at:

http://www.artspiral.org/aadt.php

Eleanor Yung and the Asian American Dance Theatre: Dancing “Asian America”

p1 In 1968, Emma Gee and Yuji Ichioka, then graduate students of the University of California Berkeley, coined the term “Asian American” through the naming of their new student organization, the Asian American Political Alliance. The organization rallied students from a diversity of Asian ethnicities and later joined student groups such as the Black Students Union at San Francisco State University to form the Third World Liberation Front. Together, they participated in the longest student strike in U.S. history advocating for the establishment of ethnic studies. The formation of the “Asian American” identity— and community— arose from a desire to unite activists of various Asian ethnicities in the U.S. to build political power; its emergence is explicitly political. During these years in the 1960s and early 1970s, an Asian American movement grew alongside the Black Liberation movement and Malcolm X as well as international liberation movements, where “the main thrust was not one of seeking legitimacy and representation within American society but the larger goal of liberation”, challenging structures of power and oppression.

p2 Within this political movement, the Asian American community underwent a cultural transformation as well, connecting modes of cultural expression with cultivating a political consciousness. “Cultural workers” such as poets, musicians, and dancers worked closely with local communities to not only critique systems of racial hierarchies and exploitation but also to create visions of bottom-up participatory democracy. For them, the goal of cultural expression and creation was both to define “Asian American” and to “serve the people” in seeking new conditions of living. One such cultural worker was the dancer and choreographer Eleanor S. Yung. Both Eleanor Yung’s choreographic works and her company Asian American Dance Theatre (AADT) built upon the Asian American movement of the 1970s to establish “Asian American” as a political identity that unites all people racialized as Asian, both domestic and abroad, and to uplift local communities through dance. However, the Orientalist views of her work held by dance critics of dominant media undermined Yung’s efforts of transforming the political landscape within Asian American communities.

Born in Shanghai in 1946 and raised in Hong Kong, Eleanor Yung studied dance starting at a young age and received training in ballet, Chinese folk dances, and Peking opera. After graduating from the University of California at Berkeley in 1969, she moved to New York City. That same year, her brother Danny Yung conducted research that revealed New York City Chinatown’s desperate need for social services as it faced economic and public safety challenges due to governmental neglect. As a response, Yung and her brother, along with Peter Pan, Frank Ching, and Rocky Chin founded the Basement Project in 1970. Drawing from the newly formed, multiethnic coalition of Asian American students on the West Coast, the Basement Project became one of the first self-identified Asian American community-based arts and activist collective in New York. The group operated under the values of reciprocity, investing heavily in the well-being of the surrounding Chinatown community to “help each other survive,” as member Tomie Arai put it. For example, it organized a health fair after noticing that many Chinatown residents lacked health care and ran weekly adult English and citizenship classes. In addition to creating supportive infrastructures for the larger Asian American community, the Basement Project functioned as a place for artists to explore and embrace their Asian American identity. Creators of various mediums, including theater, visual art, and writing, called the Basement Project their home. It is within this environment that Eleanor Yung founded Asian American Dance Theatre in 1974.

p3 Mirroring the political identity of “Asian American,” Eleanor Yung’s choreographic works and Asian American Dance Theatre as a company brought Asians of different ethnicities and nationalities together by referencing themes of the diasporic condition and transnational ties. In her 1999 essay “Moving Into Stillness,” Yung looks back on her choreographic career and notes that the landscape of Asian American dance has evolved since her involvement in the 1970s and 1980s. She asserts that “Asian American dance” follows no particular aesthetic, rather it is any dance created by a dancing Asian body in the US. and elaborates, “Asian American dance is as real and diverse as you and I.” By using the term “Asian American,” one makes a conscious decision to associate with others who may not share the same cultural (ethnic/national) background but experience similar ostracizations from being racialized as Asian. This deliberate choice makes “Asian American” and “Asian American dance” real. Just as the identity “Asian American” does not prescribe to a certain cultural marker, Asian American dance does not restrict itself to any cultural form; it welcomes the varied experiences and backgrounds that Asian American choreographers hold to shine through. Yung, herself, experimented with both traditional Asian dance forms and American modern and contemporary dance styles in her composition, blending her Chinese folk dance training with Western dance forms. However, her company also included dancers who came from or whose ethnic heritage were Chinese, Indian, Indonesian, Japanese, Korean, Filippino, and Polynesian. These dancers (company members and guest artists) choreographed pieces that were at times traditional to their heritage and at times completely experimental, covering the breadth of possibilities that is Asian American through the multiethnic and multinational dance company. It is not their dance aesthetic preferences, but the symbolism of their union, that makes AADT pieces “Asian American.”

p4 Yung’s works aligned with the larger Asian American social movement in that they spoke to issues concerning Asians in America and abroad. One of her earliest works, Ribbon Dance (1976), is based on but also deviates from traditional Chinese ribbon dance. Not only did Yung dance with black and white ribbons instead of the traditionally used red ribbons, but she also started the piece by standing directly in front and then slowly approaching the audience, which is uncharacteristic of traditional Chinese dance. Yung chose these deviations to emphasize “the presence of the totality of [her], history, culture, lineage, heritage, and [her] people.” While she refers to her Chinese heritage in speaking on the meaning behind the piece, the spotlight on Yung’s presence is distinctly political in that she confronts the audience, demanding them to take her in. She forces visibility onto the often invisibilized Chinese and Asian existence within America, asking audience members to view her and her people in their totality. Accompanied by improvisational Korean shamanistic music, Yung’s Passage (1979) reflects on the “dilemma of immigration, leaving one’s familiar home to live in an alien land, moving from one culture to another, and…transformation.” In using Korean music as a Chinese woman, Yung implies that this immigrant dilemma is shared across different Asian ethnic diasporas, thus aligning with the notion of “Asian American” as a political identity built upon shared social struggles. To explore this theme, Yung asked dancers to exit and reenter the stage with urgency, giving them no “time to think about the present, but had to constantly be aware of the immediate future and the direction they were heading.” This mimics the condition familiar to many Asian, particularly lower and working-class, immigrants who navigate (then in the 1970s and now) the racial capitalist hierarchy in America with no time except to work towards a (hopefully) brighter immediate future. Through Ribbon Dance and Passage, Eleanor Yung brought attention to the challenges that Asians in America face due to racism, both interpersonal discrimination and systemic oppression.

Passage. 1978.

Dancers: Lauren Dong and Young Soon Kim

Costume: Kwok Yee Tai

Music: Korean Shaministic

p5 In Kampuchea (1981), Yung explores another facet of the political Asian American identity: transnational solidarity with the Global South, specifically Asian countries. Kampuchea grew as a “response to the destruction of one culture by another, and its reemergence from within the aggressor,” referring to the war in Cambodia in which the U.S. involved itself. The usage of Cambodian music in responding to a crisis in Cambodia despite not being Cambodian herself highlights Yung’s understanding of the racialization of Asians in that we are flattened by the West as the same. Shared ethnicity or not, residing within the U.S. or not, we are perceived as a monocultural entity. The piece acts as a critique of American military interventions in Asia; revealing an understanding of the U.S. imperialist agenda as a factor influencing the violence in Cambodia. Yung shows heightened attention to the interconnectedness of issues plaguing Asians in regions outside the U.S. and issues affecting Asians within the U.S. As people racialized as Asian, subjects within the U.S. imperial core are immune to the effects of U.S. imperialism. Therefore, Yung asserts that we must be allies. Kampuchea exemplifies Yung and AADT’s commitment to their political consciousness as Asian Americans, extending allyship to Asians outside of the U.S. as fellow marginalized people fighting for their survival.

Ray Tadio in Yung's "Kampuchea", a more solemn modern work in 1981 on the killing during Pol Pot.

p6 In addition to building the political consciousness and identities of Asian Americans, Eleanor Yung and Asian American Dance Theatre embodied the ethos shared by radical Asian American cultural workers of “serving the people” through performance. As previously discussed, Yung believed that Asian American dance could adopt any dance style. If it was not the aesthetic that defined Asian American dance, then it was the purpose: Yung saw Asian American dance as anything that Asian communities in America (and particularly her immediate community of Chinatown) needed at the time. In the early stages of AADT, the company’s mission was to assert the validity of Asian contemporary dance choreographers in America, and Yung “choreographed Asian American dance in response to questions about where [she] came from.” However, noticing the lack of knowledge about Asian people and culture in both mainstream American society and amongst Asian people in America themselves, she “realized the purpose of the company should be to educate the public about the diversity, intricacies, artistry, and beauty of Asian dance.” Whereas AADT first focused on challenging the perception of Asian Americans as the “other”, it later switched to spreading the nuanced cultures of Asian dance to the public and most importantly, fellow Asian Americans. In generating more knowledge about one’s own culture, Yung hoped that Asian Americans would come to appreciate and reclaim their histories and cultures. This shifting of priorities within the company to meet the needs and desires of the community that they are a part of shows Yung and Asian American Dance Theatre’s deep commitment to transforming and supporting their communities. The community-oriented choreography demonstrates that Yung and her company took their role as community cultural workers seriously.

p7 Unfortunately, critics reduced the varied works of Yung and Asian American Dance Theatre to stereotypical, Orientalist viewings, missing the significance of the group to the community. Palestinian American scholar Edward Said presents the concept of Orientalism as an ideological framework in the West that presents the East as the polar opposite of Western societies. Under the lens of Orientalism, the East, or the “Orient,” is mystical and exotic; the Orient is timeless, a stagnant society stuck in the glamor of its past, unlike the West which constantly advances towards progress. Dance scholar Yutian Wong explains that “Asian Americans are not viewed as abstract bodies engaging in artistic experiments. Instead, they are seen through an Orientalist double vision in which their bodily Asian-ness must remain distanced from the modern and postmodern dance vocabularies they are using.” Asian dancers are always placed at tension with dance vocabulary of the current era, for we remain as bodies of “tradition.” As such, Asian American dance could only be seen as crossing the binary between the contemporary West and the traditions of the East.

p8 Orientalist readings appeared frequently in reviews about Eleanor Yung and Asian American Dance Theatre. In 1978, New York Times reviewer Jennifer Dunning wrote, “[t]he Asian American Dance Theatre has the unusual aim of presenting modern dance rooted in the Asian American experiences… But, sad to say, a chance was lost to communicate that particular aesthetic.” Despite having seen AADT perform in 1974, Dunning appears to have trouble considering Asian bodies and concerns to be capable of modern dance expression. She does not articulate what she imagined AADT’s “particular aesthetic” to be, but it is clear that her expectations were not met. Continuing with the review, Dunning expresses dissatisfaction with company member N.T. Yung’s experimental Movement in Pieces but did enjoy Eleanor Yung’s Passage. She applauds the piece’s “blend of traditional Asian and American modern dance gesture and movement styles” as well as the costumes’ “exotic look.” Dunning’s imagination of Asian American dance is an Orientalist one: she prescribes Asian American dance to only be the merging of traditional Asian dance with American modern dance, not recognizing the possibility of Asian dance as experimental or Asian dancers moving solely with modern dance gestures. Even in showing a preference for Passage, she does not care to mention (or was unable to detect) the underlying themes of immigration and displacement. Therefore, Eleanor Yung’s intention of expressing a collective Asian American identity through shared social challenges was lost in print. Dunning holds onto Orientalist views of Eleanor Yung, writing in 1984 that “American modern and Chinese dance blend in many of [Yung’s] works into theater that has the urgency of the first and the gestural delicacy of the second.” This review positions American dance and Chinese dance as diametrically opposed in movement quality. Following Dunning’s logic, if American dance is expansive and commanding, then Chinese dance must be intricately subdued.

p9 Other reviewers of prominent media companies expressed Orientalist sentiments as well. Doris Hering from Dance Magazine wrote about New Dance Collective in 1979, a group in which Yung participated:

Every so often a group of choreographers joins forces. Usually it is for economic reasons or to relieve the individual artists of the responsibility of an entire program. Reynaldo Alejandro, Saeko Ichinohe, Sun Ock Lee, and Eleanor S. Yung seem to have come together for a deeper reason. One might dare call it spiritual… [H]ow would one know, other than through subject matter, that the next three works were by Oriental choreographers? It was apparent in the concentration. All had great inner stillness.

Wong observes that “‘Oriental’ dancing bodies are characterized as both spiritual and unmoving,” a stereotype that Hering latches onto in her review. To her, the “inner stillness” of these Asian dancers was an innate trait, one that allowed them to be identifiable. Once more, critics racialized Yung as the stereotypical “Orient,” undermining the critical conscious-raising work she did.

p10 The late 1960s through early 1980s was a transformative period for Asians in the U.S. The concept of “Asian American” as a political alliance between all people marginalized and racialized as Asian spread from the West Coast to the East Coast, where artists such as dancer and choreographer Eleanor Yung became cultural workers building onto this movement in their art-making. For Yung, her company Asian American Dance Theatre along with her choreographic works such as Ribbon Dance, Passage, and Kampuchea supported the notion of “Asian American” as a political identity between Asians of different ethnicities and nationalities who shared the common struggle against globalized U.S. racial capitalism; and the company demonstrated their commitment as community cultural workers within the movement by adapting the themes of their repertoire to fit what they believe local Asian communities needed. In dancing the multiplicity of “Asian America” and performing community care, Yung and her company showed that dance can be a demonstration of political values and an engine for radical self and social transformation.

p11 However, prominent dance critics of the time failed to understand the political cultural labor that Yung produced. Instead, they viewed her and AADT through an Orientalist lens, writing about the aesthetic hybridity (or lack thereof) of the pieces and perpetuated images of the silent, unassuming Asian figure. Beyond the reality that Asian American history is under-studied as a whole, I wonder if these two-dimensional, Orientalist viewings of her works in dominant media have turned the Asian diasporic community, including artists and scholars, away from Eleanor Yung and Asian American Dance Theatre. Yung mentions in “Moving into Stillness” instances where audience members have walked out of performances, upset that more traditional Asian dance was performed in an Asian American dance company, as they did not consider Asian dance to be Asian American. Who were these audience members? Who is doing the Orientalizing? Is the possibility of self-Orientalization worthy of consideration? Most importantly, where are the community voices under which Asian American Dance Theatre worked for and with? Questions like these point out the gaping holes, but also opportunities, in the field of dance scholarship.

Ribbon Dance, Photographed by Tom Yahashi in Eleanor S. Yung, “Moving into Stillness,” Edited by Sharon K Hom, Chinese Women Traversing Diaspora, 1999, 174.

.png)

By

By

July 31, 2023

July 31, 2023

0 comments