This review by Roberta Lord on AAAC was written long ago but it is more

comprehensive than other reviews posted here. Recently rediscovered, it sheds an

interesting light on AAAC's work.

Robert Lee, executive director of New York City's Asian American Arts Centre

(AAAC), was an undergraduate physics major at Rutgers University in the 1960s. One summer he took an art course taught by a Sinologist who also happened to be an artist. “An artist teaching art history somehow communicates things that are not verbal,” Lee remembers. He switched his major to studio art and art history, finished his bachelor degree, and moved to Chinatown. "I worked here and took part in the activism of the anti-Vietnam War movement and the civil rights movement. Given the politics of the time, I thought it was more important to be in the community than to try to work on these issues in academia."

At first, he says, “I didn't know how to use what I had learned.” Slowly he began to envision a bridge linking the past to the present and the future.

In the middle of all the political activity and community activity and arts activity, I began to relate these Asian American artists I was seeing to what I had learned in school. These artists would be the beginning. They would not remain an insignificant minority. They would mean something, and they would mean something in relationship to everything I had learned about the founding cultures of China, India and the West. And so we started to make a collection, an archival collection, and then a few years later we started to look at artists who were difficult to collect because they were in their later years or had passed away.

The AAAC occupies 2500-square-feet of loft space on the third floor at 26 Bowery, just south of Canal Street, in the heart of Chinatown. The non-profit organisation's focus has shifted over the last twenty-five years from dance to the visual arts. Lee has directed visual arts programming since 1978. He instituted the first Asian American artist slide archive in the United States. The archive functions as a registry of over 700 Asian American artists as well as a permanent historical record of their works and their development. It is used by national and international publishers, curators, art consultants and community organizations.

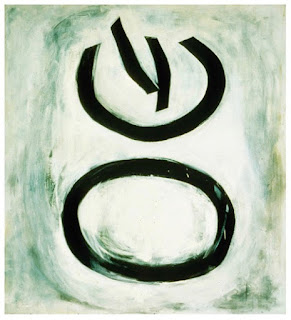

Earl Jung Reflections Oil on Canvas 1961 63 x 58” 7th AAAC Annual: Stream Segment: The Reintegration of Tradition in Contemporary Art 1997

Despite the inevitable struggles for funding, the exhibitions at the AAAC proceed with boldness, freshness and faith. Lee maximizes available resources by putting together two-to-four-person exhibitions that serve as visual conversations around unifying themes. These conversations are enhanced in brochure essays by Lee and invited critics, and in the related panel discussions and/or gallery tours.

The exhibition “Three Generations: Towards an Asian American Art History” in 1997 showed three painters—Tseng Ta-Yu, Phillip P. Chan and Theresa Chong—whose works are stylistically dissimilar but who as artists are linked by a daisy chain of mentorship. “Stream Segment: The Reintegration of Tradition in Contemporary Art” in 1997 included work by non-Asian artists who had taken Asian subject matter and/or iconography as their point of departure. "Silk Light: 4 Artists from Korea” in 1998 was provoked by the Korean phrase “walking in silk robes in the evening moonlight,” which, according to Lee's accompanying text, “describes the passion and futility of the artistic impulse in the absence of the beholder. Such is the situation here. Such is the situation of Seoul, Korea." The AAAC's exhibition titles are always poetic and provocative: in 1996 the sixth annual group show of the work of a dozen artists selected from the archive was called “Twelve Cicadas in the Tree of Knowledge.”

The ongoing "Milieu” project (Parts I and II have already occurred, Part III was recently funded by a National Endowment for the Arts grant), focuses on artists active in the two decades after the Second World War. It is based on a national research project, “Asian American Artists and Their Milieu: 1945-1965,” undertaken by the AAAC in 1987 with support from the New York State Council on the Arts and the Rockefeller Foundation.

In addition to its work with contemporary and post-war artists, the AAAC also researches and presents folk arts. In a recent statement about the folk arts program, Lee describes traditional arts as:

art practices with spiritual, ethical, health and communal components. Far from naïve, these folk art/life practices serve to maintain a satisfying balance in life. The Arts Centre is mindful of traditional art's potential to offer contemporary perceptions an equanimity that has eluded the stress of modern conceits and the pursuit of excellence.

The 12 March 1986 issue of Nation magazine reported that Chinese Minister of Culture Wang Meng (who resigned after the Tiananmen Square massacre), said about his 1986 visit to the United States: “I am deeply impressed by the interest and friendliness of Americans towards the Chinese people, but I am appalled by their lack of knowledge about us.” Americans are not necessarily any better educated about their own countrymen who are of Asian descent. New York City has the largest Asian American population in the United States. Asian Americans represented 7 percent of the city’s total population in the 1990 census, and 12.2 percent of the population of the borough of Queens. Yet as Village Voice writer Andrew Hsiao pointed out in a 23 June 1998 article about Asian American activism, hollow stereotypes of Asian Americans prevail. “Indeed, portraits of Asian Americans as victimized sweatshop toilers or Ivy League drones connect to a long history of painting Asian Americans as poster children for the Horatio Alger version of America.”

Amy Loewan at Horace Mann School detail 2017

Lee finds that a similar confusion reigns in the visual arts. In a recent exhibition essay he wrote, "Despite many efforts to do otherwise, the voice of artists and thinkers from Asia continues to be reinterpreted or modulated for western ears. Assorted expectations, oppression of ethnic communities, nationalistic intentions, agendas based on disinformation as much as on confusion, continue to make it difficult to hear them.” If the blurring of Asian American identity in the United States can be likened to a storm, then Lee works to maintain the AAAC as that storm's calm centre.

It's like Captain Kirk in an electrical fog and none of your instruments work and you can't tell where you're going and so you have no names and nothing works and so you just fly by your ears and that's where I think many artists find themselves. I think that's exactly where we are, too. All we have are the words from the last period of time that we knew. I use those words as much as I can ... to be helpful ... to let people know the nature of this fog.

The AAAC is distinctly and deliberately an enclave. If it lost this identity, if it moved uptown or even across town, it would lose its bearing altogether. Although Lee understood early on that he could have exploited his expertise in the larger, diluted world of art curatorship—in mainstream educational institutions, museums or galleries—he opted to maintain a local, concentrated presence in the heart of a major Asian American community. He believes that being there, in the heart, plays and will continue to play an important role for both community members and for emerging and established Asian American artists.

.png)