The Asian American Arts Centre: Its History 1974-2002

Setting the Context…

AAAC has decided this summer (of 2019) to revisit an essay by independent writer, Yo Park (Young Park) in June of 2002. It was written for the AAAC Story Exhibition (May 23- July 13, 2002) and NYU Conference - The Players: Asian American Arts, During this time, the Centre did not have the funding to hire an editor, and as a result this paper was put on hold. This paper mentions how the Centre was experiencing a cut in funding from our local community supporter. This was due to the Centre was becoming a citywide known organization after the media recognition of the CHINA: June 4, 1989 show and thus less eligible to receive the grant.

Since this paper was written, the LMDC (Lower Manhattan Development Corporation) grant came in 2007 to develop artasiamerica, AAAC’s free online archive. In 2009, the AAAC lost the struggle to keep its 26 Bowery space, our home, performance and gallery since 1976. Now, the AAAC has shifted its goal from becoming a museum into finding new homes for the permanent collection. This paper is important as it marks AAAC in 2002 and all that the Centre has accomplished; including its work in Folk Arts, in Asian American dance, in countless exhibitions and advocacy for community life. It was also the first to mention the relation of Godzilla to AAAC and how it emerged. While this paper has been put to the side, the Centre still holds value to all that is mentioned and thanks Yo Park for writing this back in 2002.

Following the paper will be a few images throughout the years including images taken after this paper was originally written.

The Asian American Arts Centre: Its History 1974-2002

by Young Park, 2002

Edited by Maxine Bell

Introduction

After almost three decades of running an arts organization for the Asian American community, a reflection of Robert Lee, Director of the Asian American Arts Centre, is, "Yes, it is okay to be an Asian-identified artist in America. It is not the choice every Asian American artist will make, nor do I suggest it should be. However, it bears the blessings of the Asian past, and there are many artists who want that." Lee’s reassuring spirit and the voice of confidence from which he speaks reveals that he has learned, through many the challenges and adversities, how to masterfully relinquish all the psychologically discouraging elements to move ahead with human dignity and integrity. As it celebrates its 28th anniversary, the Asian American Arts Centre’s struggles and triumphs offer lessons and inspiration, specifically for “minority” organizations, but no less for others whose place in the cultural fabric of America is a continuous process of careful re-weaving.

Overview

Since it was founded in 1974, the Asian American Arts Centre has existed in Chinatown as a community cultural site, introducing and presenting traditional arts and cultures through contemporary performance, hosting exhibitions, and engaging in public education, offering a rare synthesis of Western and Asian art forms. For more than two decades before the current multicultural and global era arrived, the AAAC focused on resisting the many barriers in place to neglect “ethnic” artists’ access to cultural and social opportunities. The Arts Centre embraced artists within the large Asian and Asian American diaspora, who were not able to find other ways to enter the art world in the United States, primarily by providing an exhibition space for them to release their artistic desire and aspiration. It was not an easy task to support and advocate for a minority art community for non-profit purposes, especially at a time when mainstream art organizations were structured for social, cultural, and economic systems that rarely allowed any accessibility for ethnic communities.

In spite of such difficulties, in the years since its inception, the highly motivated spirit present at the beginning changed into a staunch regularity, and the struggle and anguished frustration was then transformed into an experienced readiness. Through all these changes, the Asian American Arts Centre never stopped focusing on advocating Asian American Art.

Being such a pioneering place for those of an Asian identity, the AAAC’s first two decades, was, in some ways, limited in that it had to mostly focus on helping Asian American artists express their anger and anguished confusion against the unfairness of the American cultural and social system. Since the mid 1990’s, however, as the international cultural climate towards ethnic cultures changed in a favorable direction, the recognition of cultural difference emerged as a new unifying ethos in American society as well as for the whole world. Along with this process, the programming direction of the Centre slowly changed from a one-sided critical and victimized stance, to a mutually encouraging and supporting position between all peoples, in order to aid the development of a better human perspective.

Influenced by current theory regarding cultural diversity now prominent in the field of cultural studies, AAAC’s mission has developed from a general effort to promote Asian American cultural growth, to highlighting its historical and aesthetic linkage to other communities by specifically and strategically raising color consciousness among people as a public ethic.

The AAAC’s work has brought to the Centre a number of ethnically Asian artists of a new generation, who exhibit a wide variety of different imaginations and creative capacities, which reflect changing global aesthetics. In this process, the existence of the Asian American Arts Centre and its contribution to the New York art world has begun to be recognized and covered by major news media.

AAAC has emerged again at the forefront of Asian American art, pushing the issue of identity to a new level of inclusion and leading the way as a space that, in the words of Robert Lee, overcomes “a limited sensibility of resistance, and assumes the responsibility of a re-envisioned, diverse center.” It is out of strength that Asian art will find its place in our new global society.

The Early History of the Asian American Arts Centre: The Asian American Dance Theater (AADT) and the Asian Arts Institute (AAI)

It was not until 1987 that AAAC had its present name. Eleanor S. Yung, a performer, choreographer and educator, under the name of the Asian American Dance Theater, founded AAAC in 1974. AADT was a not-for-profit organization, which promoted Asian and Asian-influenced traditional and contemporary dance, expressing the variety of heritages from Asia and building on traditional dance forms. With a background in Chinese classical dance, western ballet, and American modern dance, Yung had pursued an ongoing program of cross-cultural art in contemporary life. Yung applied Asian traditional elements in form, story, rhythm and sensibility, synthesized with the sweep and structural rigor of American modern dance. The traditional dances of India, Bali, China, Indonesia, Korea, Japan and the Philippines were combined with contemporary dances inspired by Asian themes.

AADT nurtured Asian and Asian American choreographers and performers extensively through presenting series in the United States in settings ranging from concert stages in colleges to outdoor festivals. It became a focal point for the majority of Asian dance masters who came to the dance capitol of New York. Around 1987, it was widely recognized that Yung was instrumental in bridging a traditional repertoire featuring folk and classical dances from Asia and a contemporary repertoire that evokes Asian forms and sensibilities. This small experimental group in New York’s Chinatown had become a nationally acclaimed group of young adults proclaiming their Asian cultures through traditional and contemporary dance. Yung’s signature piece “Passage” received high acclaim, and her choreography is collected on video at the Lincoln Center Library for the Performing Arts in New York City.

AAAC’s stance also drew from Edward Said's cultural theory of Orientalism, which details American culture's fascination with the mystique and exoticism of Asian cultures, and explains how it serves both to attract and appropriate what is desirable, and hide and deny what does not enhance and contribute to America's own self image, making this type of attention a double-edged sword. Lee explains:

The artists’ slide archives, begun in 1982, was a pioneering effort to raise visibility. As the first Asian American slide archives in the United States, it has functioned as a registry of over 700 Asian American artists (1,700 in 2018) as well as a permanent historical record of their works and their development. As such, it has become a resource for national and international publishers, curators, art consultants and community organizations. The Centre also incorporated Chinese folk art into its programs in 1985. Recognizing the importance of tradition as a vital puzzle piece in identity. Lee describes traditional arts as:

The Arts Centre has also continued the ongoing ‘Milieu’ project. Part I (1993) and II (1996) have already occurred, Part III (2000), which was recently funded by a National Endowment for the Arts grant, focuses on artists active in the two decades after the Second World War. The Milieu series is based on a national research project, ‘Asian American Artists and Their Milieu: 1945-1965,’ undertaken by the AAAC in 1987 with support from the New York State Council on the Arts and the Rockefeller Foundation. Similarly, Betrayal/Empowerment Part 1(1994) exhibited works by artists who began their careers in the 1950s and 60s. In addition, Three Generations: Towards an Asian American Art History (1997) also worked on a mentoring relationship that spans the post WWII era to the present, from San Francisco to Oberlin to New York.

AAAC and the Tiananmen Square Massacre

In the summer of 1989, AAAC kept a close watch on the student pro-democracy movement in China. After the tanks rolled into Beijing’s Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989, Lee believed that Tiananmen was of cultural significance because it not only changed how people felt about China, but it was also connected to issues of basic human dignity. The Centre responded almost immediately to the June 4 attack by promoting an exhibit whose art would continue to nourish public protest against the Chinese government. 5000 flyers were sent around the country inviting artists and non-artists of all ages to submit visual art or poetry on the event, to be rotated, gathered, and documented. The art would be gathered to become part of a permanent collection.

CHINA: June 4, 1989 co-sponsored with P.S. 1, opened at the Blum Helman Warehouse in New York, and went on to tour to Mexic-Arte in Austin, Texas, Cleveland Institute of Art in Cleveland, Ohio, and Buckham Gallery in Flint, Michigan in 1994. Previously, a portion went to Hong Kong in 1990. It included photographs, sculptures, and conceptual pieces as well as a large-scale takeoff on Picasso’s Guernica by Asian American artist Ling Ling. The centerpiece of the show was a series of doors displaying artwork on both sides, joined together to be a new "Great Wall of China" - a wall of protest and sorrow. While the linking of panels suggested a tangible means of collaboration and hope for the future of China, the effort was a memorial, similar in some ways to the Names Project, the vast quilt made up of individual squares commemorating those who have died of AIDS. 74 doors were on view originally; eventually some 171 doors were on display. "Arts in America," a national arts magazine, mentioned it as one of the major exhibitions of the year.

Tiananmen Square served ironically to educate AAAC about ongoing domestic roadblocks to artistic freedom. Asked to show CHINA, June 4, 1989 in Washington, D.C. at the Russell Rotunda on Capitol Hill in the summer of 1990, Lee was confronted with a request for the removal of three works. Both sponsors of the exhibition, the private, non-profit Congressional Human Rights Foundation and the office of Senator Ted Kennedy, Democrat of Massachusetts, objected to the paintings on moral and religious grounds. Faced with this demand for censorship, Lee withdrew the entire American portion of the show a week before the scheduled opening.

Believing that the meaning and the gravity of Tiananmen Square would have a long-term impact, Lee intended to organize the political and cultural community around this issue. He was disappointed, however, in a lack of press coverage after the show opened in Flint, Michigan. "It seemed like after Tiananmen Square was out of the media spotlight, it was treated like a dead issue." However, its impact would continue to influence the growth of Asian art in America. As Ming Mur-Ray, a Hong-Kong born artist who participated in the CHINA: June 4, 1989 exhibition, indicated that this exhibit was influential and showed the participating Asian artists that they could draw strength from their identity and that they could use it as a theme in their art. (In 2019, the Centre reflects on CHINA: June 4, 1989 in a new blog article and Youtube video.)

AAAC and Godzilla

In the early ‘90s, major institutions such as the New Museum and the Asia Society in New York City finally recognized the cultural movement in Asian American communities. When they organized exhibitions under the name of “art of identity”, they adopted the issues of the movement as their major theme or part of it. Other groups arose insisting on the recognition of the complexities and delicacies of the Asian American diaspora. One hundred to two hundred Asian American artists gathered in the early '90s, and an artistic network, known as Godzilla (1974), began holding monthly meetings to discuss identity and other related concerns.

Godzilla’s major leading members including, Margo Machida, Carol Sun, Yong Soon Min and Bing Lee were employees or Artists in Residence who made a lot of contribution to the development of the Asian American Arts Centre. The Centre’s effort to establish a place for Asian American artists and their work had played a tremendously important role in the emergence of Godzilla. AAAC had never stopped helping exert pressure on mainstream institutions to change and make the American public aware of cultural developments in Asian American communities. Unfortunately, the Asian American Arts Centre was denied proper credit by the group. Recognition between these organizations was a power struggle that lasted almost for a decade.

It was difficult to organize the arts community politically due to the lack of a unifying vision that encompassed all peoples. The story of ethnicity in the arts was easily labeled as ethnic separatism and was used as an excuse to downplay its validity as serious contemporary art. Funds were cut and supporters burned out or took other avenues. It began to be time for an alternative vision to replace the idea of art of identity as a sole focus.

If Godzilla and the Asian American Arts Centre had collaborated under an umbrella of one organization and been conscious of leaving their legacies to their post generations, the Asian American Art community could have been much more powerful and generated a stronger impact in the cultural field of the United States. Such a chance will come again to the Asian American community in the near future. The lesson between Godzilla and the Asian American Arts Centre would make their next generation vigilant and alert of their opportunities for forming a solid cultural unit of Asian American Art in the United States and contributing to our better world.

Lee recollects about this long period of retrenchment as follows:

Despite the inevitable struggles for funding, the exhibitions at the AAAC proceeded with boldness, freshness and faith. Maximizing available resources, the Centre never stopped putting together two to four person exhibitions that served as visual conversations around unifying themes.

Important Exhibitions in the ‘90s

The important exhibitions at this time were Passion and Compassion (1996); Three Generations: Towards an Asian American Art History (1997); Inside One (1998); the Day and Night Transparent AAAC 8th Annual (1998); 7lb 9oz: The Reintegration of Tradition into Contemporary Art (1999); and Power Print (2001).

7lb 9oz:The Reintegration of Tradition into Contemporary Art reflected AAAC’s renewed assurance and different perspective. In the exhibition brochure, Lee wrote:

According to Lee, they assert the Asian presence of difference. Ethnicity is neither conservative, closed, or traditional; it is dynamically changing in the contemporary world and capable of creating new forms:

Lee concludes by saying that this is a notion at the heart of every religion, at its primordial mystical core:

Art critic of the NYT, Holland Cutter, noticed AAAC’s confidence and renewed stability of direction. Cutter emphasized in his review that Lee had based his exhibition title, 7lb 9oz:The Reintegration of Tradition into Contemporary Art, on the weight of a newborn baby, a symbol of the rebirth and continuation of Asian traditions in art produced outside of Asia itself. It was the first coverage of the organization’s exhibition by the newspaper and since then, its exhibitions have continued to be reviewed.

The windfall of a group of young artists, whose refreshing creative ideas and sensitivities followed this significant breakthrough, awakened Lee’s colorful and radiant sensibility, which had been in hibernation for a long period of time. Works created ranged from conceptual video exploring ideas such as the inside and the outside, death and life, and examining social constructs, to multi-media installations reclaiming both ordinary and discarded industrial materials such as cardboard boxes. The subjects and the mediums they dealt with were abundant. These artists proved that they didn’t have to depend on their Asian identity to create their works. As Holland Cutter said, "there’s nothing necessarily ‘Asian’ about their works."

The dilemma of difference, however, still remained for the Centre as long as powerful elements in America refused to hear other modalities, insisting on a national identity and a hierarchy that does not give credence to multiculturalism as an important if not defining description of the US. Lee believes in the absolute necessity of a voice from those who live on the fringe and know well what it means to be neutralized and manipulated.

In light of this continuing struggle, Lee now proposes a different American ethos. It is an awareness-of-self in the context of a cultural past. For once one accepts oneself as such, an individual of color has the basis to accept and embrace other individuals and cultures. The multiple perspectives that now compose the American landscape and the global context can be accepted and recognized as a non-hierarchical basis for dialogue and cultural development. Given this perspective, the phrase, 'culturally specific organizations' is a misnomer since for in such organizations, specific cultural roots serve as points of departure to see and embrace the whole.

Conclusion

The Asian American Arts Centre has successfully matured, maintaining a symbiotic collaboration with its ethnic community and becoming a role model of community cultural organization. Located in Chinatown, it has been a focal point for cultural and artistic activities of both community members and artists. With long years and difficult stages of passing through of its development, the Centre’s perspective and management skills have matured and refined to the extent that its exhibitions are often evaluated parallel to quality exhibitions of major mainstream organizations. Thus, expanding the accepted definition of a community arts organization.

Even though our globalized economy and politics require us to recognize and accept cultural diversity and the differences of our world, White supremacy still prevails. The orthodox cultural and racial standard of White America runs on cultural oppression.

Color consciousness is the critical effort to open the mind and heart to acknowledge differences in cultures, treatment, privileges, and experiences. Cultural critics in the mainstream academic field have labored long and hard to educate the public on how color and physical disability have unfairly influenced life opportunities. Considering its long history of dealing with the issue of cultural difference, experiencing all the obstacles of being neglected and struggling as well as ultimately regaining its dignity and vitality, it is not hard to believe the Asian American Arts Centre will continue to add dimension to this movement.

Ideally, when the cultural and political policy of the mainstream critical field and the mission of community cultural organizations go hand in hand, the community groups will then have a closer connection and valid role within mainstream culture. However, this is not the reality. The government agency the AAAC depends on for grants now believes that the Centre can no longer be considered eligible as a local community organization due to the attention the Centre received from major news media.

It is time, however, to redefine the role of ethnic community organizations. The Asian American Arts Centre needs to exist and be supported as a community based arts organization. Their longstanding role of educating and supporting their ethnic community needs to be generously expanded to include their mediating and negotiating role between the community and the mainstream. Their purpose is not complete until the mainstream society reflects the reality of this county’s makeup. The Centre should be encouraged to work towards harmony, continuously creating a chain of vibrantly multi-cultural products filled with excitement, empowerment, and communication.

AAAC has decided this summer (of 2019) to revisit an essay by independent writer, Yo Park (Young Park) in June of 2002. It was written for the AAAC Story Exhibition (May 23- July 13, 2002) and NYU Conference - The Players: Asian American Arts, During this time, the Centre did not have the funding to hire an editor, and as a result this paper was put on hold. This paper mentions how the Centre was experiencing a cut in funding from our local community supporter. This was due to the Centre was becoming a citywide known organization after the media recognition of the CHINA: June 4, 1989 show and thus less eligible to receive the grant.

Since this paper was written, the LMDC (Lower Manhattan Development Corporation) grant came in 2007 to develop artasiamerica, AAAC’s free online archive. In 2009, the AAAC lost the struggle to keep its 26 Bowery space, our home, performance and gallery since 1976. Now, the AAAC has shifted its goal from becoming a museum into finding new homes for the permanent collection. This paper is important as it marks AAAC in 2002 and all that the Centre has accomplished; including its work in Folk Arts, in Asian American dance, in countless exhibitions and advocacy for community life. It was also the first to mention the relation of Godzilla to AAAC and how it emerged. While this paper has been put to the side, the Centre still holds value to all that is mentioned and thanks Yo Park for writing this back in 2002.

Following the paper will be a few images throughout the years including images taken after this paper was originally written.

The Asian American Arts Centre: Its History 1974-2002

by Young Park, 2002

Edited by Maxine Bell

Introduction

After almost three decades of running an arts organization for the Asian American community, a reflection of Robert Lee, Director of the Asian American Arts Centre, is, "Yes, it is okay to be an Asian-identified artist in America. It is not the choice every Asian American artist will make, nor do I suggest it should be. However, it bears the blessings of the Asian past, and there are many artists who want that." Lee’s reassuring spirit and the voice of confidence from which he speaks reveals that he has learned, through many the challenges and adversities, how to masterfully relinquish all the psychologically discouraging elements to move ahead with human dignity and integrity. As it celebrates its 28th anniversary, the Asian American Arts Centre’s struggles and triumphs offer lessons and inspiration, specifically for “minority” organizations, but no less for others whose place in the cultural fabric of America is a continuous process of careful re-weaving.

Overview

Since it was founded in 1974, the Asian American Arts Centre has existed in Chinatown as a community cultural site, introducing and presenting traditional arts and cultures through contemporary performance, hosting exhibitions, and engaging in public education, offering a rare synthesis of Western and Asian art forms. For more than two decades before the current multicultural and global era arrived, the AAAC focused on resisting the many barriers in place to neglect “ethnic” artists’ access to cultural and social opportunities. The Arts Centre embraced artists within the large Asian and Asian American diaspora, who were not able to find other ways to enter the art world in the United States, primarily by providing an exhibition space for them to release their artistic desire and aspiration. It was not an easy task to support and advocate for a minority art community for non-profit purposes, especially at a time when mainstream art organizations were structured for social, cultural, and economic systems that rarely allowed any accessibility for ethnic communities.

In spite of such difficulties, in the years since its inception, the highly motivated spirit present at the beginning changed into a staunch regularity, and the struggle and anguished frustration was then transformed into an experienced readiness. Through all these changes, the Asian American Arts Centre never stopped focusing on advocating Asian American Art.

Being such a pioneering place for those of an Asian identity, the AAAC’s first two decades, was, in some ways, limited in that it had to mostly focus on helping Asian American artists express their anger and anguished confusion against the unfairness of the American cultural and social system. Since the mid 1990’s, however, as the international cultural climate towards ethnic cultures changed in a favorable direction, the recognition of cultural difference emerged as a new unifying ethos in American society as well as for the whole world. Along with this process, the programming direction of the Centre slowly changed from a one-sided critical and victimized stance, to a mutually encouraging and supporting position between all peoples, in order to aid the development of a better human perspective.

Influenced by current theory regarding cultural diversity now prominent in the field of cultural studies, AAAC’s mission has developed from a general effort to promote Asian American cultural growth, to highlighting its historical and aesthetic linkage to other communities by specifically and strategically raising color consciousness among people as a public ethic.

The AAAC’s work has brought to the Centre a number of ethnically Asian artists of a new generation, who exhibit a wide variety of different imaginations and creative capacities, which reflect changing global aesthetics. In this process, the existence of the Asian American Arts Centre and its contribution to the New York art world has begun to be recognized and covered by major news media.

AAAC has emerged again at the forefront of Asian American art, pushing the issue of identity to a new level of inclusion and leading the way as a space that, in the words of Robert Lee, overcomes “a limited sensibility of resistance, and assumes the responsibility of a re-envisioned, diverse center.” It is out of strength that Asian art will find its place in our new global society.

The Early History of the Asian American Arts Centre: The Asian American Dance Theater (AADT) and the Asian Arts Institute (AAI)

It was not until 1987 that AAAC had its present name. Eleanor S. Yung, a performer, choreographer and educator, under the name of the Asian American Dance Theater, founded AAAC in 1974. AADT was a not-for-profit organization, which promoted Asian and Asian-influenced traditional and contemporary dance, expressing the variety of heritages from Asia and building on traditional dance forms. With a background in Chinese classical dance, western ballet, and American modern dance, Yung had pursued an ongoing program of cross-cultural art in contemporary life. Yung applied Asian traditional elements in form, story, rhythm and sensibility, synthesized with the sweep and structural rigor of American modern dance. The traditional dances of India, Bali, China, Indonesia, Korea, Japan and the Philippines were combined with contemporary dances inspired by Asian themes.

AADT nurtured Asian and Asian American choreographers and performers extensively through presenting series in the United States in settings ranging from concert stages in colleges to outdoor festivals. It became a focal point for the majority of Asian dance masters who came to the dance capitol of New York. Around 1987, it was widely recognized that Yung was instrumental in bridging a traditional repertoire featuring folk and classical dances from Asia and a contemporary repertoire that evokes Asian forms and sensibilities. This small experimental group in New York’s Chinatown had become a nationally acclaimed group of young adults proclaiming their Asian cultures through traditional and contemporary dance. Yung’s signature piece “Passage” received high acclaim, and her choreography is collected on video at the Lincoln Center Library for the Performing Arts in New York City.

In 1979, after studying with the sinologist George Weber, having participated in Basement Workshop and the Chinatown Street Fair, and managing the visual arts program of Manpower’s CETA project, Robert Lee joined Yung, changing AADT’s name to the Asian American Dance Theater/Asian Arts Institute (AAI). As the director of AAI, he began to vigorously support its visual arts programming by developing an annual series of contemporary art exhibitions, creating an archival resource on Asian American visual artists, and supporting a folk arts research and presentation project. A political as well as aesthetic approach informed the Institute’s development at this early stage, as he shares in this recollection:

In the early 1970's, the disaffection with government policies, the Vietnam War, and the civil rights movement all contributed to the view that major institutions had left out a piece of American history and were not serving a distinct segment of the population. This demanded of people of color that they uncover for themselves their own story. The history of Asians in America was one of these. The Arts Centre chose to present and explore our community in the Lower East Side of New York. The concept of Asian American art is ethnic, cultural and political, a middle ground whose value awaits recognition. Asian American art is in the middle of a river, so to speak, of political, cultural, and artistic complexities. It is a way of looking at art that is not only Asian and not only American, nor simply artistic, but a combination of these. Its implications require the choice of a different ethical stance; we chose community action.

|

| AAI life drawing class, 1981. |

Modern art, as it has evolved in the technologically oriented West, has often turned to Asia and its collective artistic ideas for new sources of inspiration. Along with the influence of technology and industrialization, the indigenous moral and ethical values of Asia are in this way uprooted, and historic patterns of meaning and symbolic systems degraded… And despite many efforts to do otherwise, the voice of artists and thinkers from Asia continues to be reinterpreted or modulated for Western ears. Assorted expectations, oppression of ethnic communities, nationalistic intentions, agendas based on disinformation as much as on confusion, continue to make it difficult to hear them.

In this context, the purpose of the organization became focused on having Asian Americans see the value and importance of their own heritage, in whatever capacity that may be, and revive it:

Asian artists in America, who have been nurtured by our modern milieu, are in a unique position to draw from both Eastern and Western sources. These artists are pioneers of a new art that has important implications for people in Asia.

For Asians who live in a Western context, the work of these artists is especially valuable. The Americans’ mass media environment makes it almost impossible for an Asian minority to see current images of themselves, to identify and know themselves, and to see their beliefs and values expressed in tangible forms. The work of Asian American artists must be acknowledged and supported, especially by Asians in leadership roles, to enable younger generations to retain meaningful connections with their Asian heritage. Eastern and Western experiences, street life and sounds of both cultures have always been available to them and are part of their store of memories. A rich resource, people who are bi-cultural have something special to offer.

In 1987, AADT/AAI announced the new name of the organization, the Asian American Arts Centre (AAAC). Although the annual New York Dance Season, presented since the organization’s inception, continued to be a fixture, the change in name reflected a shift from the early focus on dance to one of visual arts. Visual arts classes, an exhibition series, artists’ slide Archives and the Artists-in-Residence program were begun and nurtured over the years. The AAAC’s publication, Artspiral, with its focus on visual art was launched in 1988.

Lee recalls the beginning of AAAC’s Annual Series of Exhibitions, one of the most important and influential events of the center:

The Annual series of exhibitions began in 1985, as "Ten Chinatown: First Annual Open Studio Exhibition" with Ai Wei Wei's participation (when he was still unknown). The role of the Annuals/Open Studios in the Asian American Arts Centre's visual arts program was an opportunity to exhibit many artists, often quite diverse, eclectic and innovative. But we never lost sight of our mission: to bring attention to a particular kind of artist who we believed had been overlooked. AAAC always sought to raise the visibility of the presence of difference.

Panel discussions held in conjunction with each exhibition served to enhance the public’s understanding and involvement. Since the recreation of the program in 1982, hundreds of artists have participated in over eighty exhibitions. Critical exhibitions, which clearly reflected the organization’s programming direction and had great public impact included; Emily, Anna and Ti Shan: the First Generation (1985); Dreams and Fantasies (1985); Orientalism (1986); The Mind’s I, Part 1,2,3 & 4 (1987); Public Art in Chinatown (1988); Voilence of Victory (1991); And He Was Looking For Asia: Alternatives to the Story of Christopher Columbus (1992); Betrayal/Empowerment Part I (1994); and Ancestors: a Collaborative Project with Kenkeleba House (1995).

|

| Taken at The Mind's I Part 1 opening (1987). Second from the right is artist, Albert Chong. |

|

| Artists Arlan Hwang and Martin Wong with Robert Lee at Mind's I Part 1 opening. |

Art practices with spiritual, ethical, health and communal components. Far from the stereotype of being a naive expression of limited value, these folk art/life practices serve as exemplars of a satisfying balance in life. The Arts Centre is mindful of traditional artists’ potential to display an equanimity that has eluded many of us through the stress of modern conceits and the pursuit of so-called sophisticated ideals of excellence.

With this value in folk arts in mind, the Chinese Folk Arts Presentation and Research program was begun, including the Annual Chinese New Year Folk Arts Festival, and the Chinese Folk Arts Video Documentation begun in 1989. Folk artist and farmer from Toisan County in the Pearl River Delta, Uncle Ng Sheung Chi won national recognition in 1991 after AAAC's documentary about him, “Uncle Ng Comes to America”. (His book, “Uncle Ng Comes to America” was not published until 2014. More on this project can be seen here.)  |

| January 1989, Chinese Shadow Puppet expert, Jo Humphrey (pictured middle) with a shadow puppet in the first Sharing Folk Arts event at AAAC Gallery (woodblock prints are on the walls behind them). |

The Arts Centre has also continued the ongoing ‘Milieu’ project. Part I (1993) and II (1996) have already occurred, Part III (2000), which was recently funded by a National Endowment for the Arts grant, focuses on artists active in the two decades after the Second World War. The Milieu series is based on a national research project, ‘Asian American Artists and Their Milieu: 1945-1965,’ undertaken by the AAAC in 1987 with support from the New York State Council on the Arts and the Rockefeller Foundation. Similarly, Betrayal/Empowerment Part 1(1994) exhibited works by artists who began their careers in the 1950s and 60s. In addition, Three Generations: Towards an Asian American Art History (1997) also worked on a mentoring relationship that spans the post WWII era to the present, from San Francisco to Oberlin to New York.

|

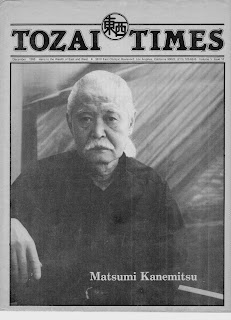

| North Wind, Matsumi Kanemitsu, 36x24.5, lithograph, 1977. |

|

| Kanemitsu in the Tozai Times, 1988. Kanemitsu was included in the Milieu Part II show in 1996 |

AAAC and the Tiananmen Square Massacre

In the summer of 1989, AAAC kept a close watch on the student pro-democracy movement in China. After the tanks rolled into Beijing’s Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989, Lee believed that Tiananmen was of cultural significance because it not only changed how people felt about China, but it was also connected to issues of basic human dignity. The Centre responded almost immediately to the June 4 attack by promoting an exhibit whose art would continue to nourish public protest against the Chinese government. 5000 flyers were sent around the country inviting artists and non-artists of all ages to submit visual art or poetry on the event, to be rotated, gathered, and documented. The art would be gathered to become part of a permanent collection.

|

| "Deng," Untitled, Painting from Square. |

CHINA: June 4, 1989 co-sponsored with P.S. 1, opened at the Blum Helman Warehouse in New York, and went on to tour to Mexic-Arte in Austin, Texas, Cleveland Institute of Art in Cleveland, Ohio, and Buckham Gallery in Flint, Michigan in 1994. Previously, a portion went to Hong Kong in 1990. It included photographs, sculptures, and conceptual pieces as well as a large-scale takeoff on Picasso’s Guernica by Asian American artist Ling Ling. The centerpiece of the show was a series of doors displaying artwork on both sides, joined together to be a new "Great Wall of China" - a wall of protest and sorrow. While the linking of panels suggested a tangible means of collaboration and hope for the future of China, the effort was a memorial, similar in some ways to the Names Project, the vast quilt made up of individual squares commemorating those who have died of AIDS. 74 doors were on view originally; eventually some 171 doors were on display. "Arts in America," a national arts magazine, mentioned it as one of the major exhibitions of the year.

Tiananmen Square served ironically to educate AAAC about ongoing domestic roadblocks to artistic freedom. Asked to show CHINA, June 4, 1989 in Washington, D.C. at the Russell Rotunda on Capitol Hill in the summer of 1990, Lee was confronted with a request for the removal of three works. Both sponsors of the exhibition, the private, non-profit Congressional Human Rights Foundation and the office of Senator Ted Kennedy, Democrat of Massachusetts, objected to the paintings on moral and religious grounds. Faced with this demand for censorship, Lee withdrew the entire American portion of the show a week before the scheduled opening.

Believing that the meaning and the gravity of Tiananmen Square would have a long-term impact, Lee intended to organize the political and cultural community around this issue. He was disappointed, however, in a lack of press coverage after the show opened in Flint, Michigan. "It seemed like after Tiananmen Square was out of the media spotlight, it was treated like a dead issue." However, its impact would continue to influence the growth of Asian art in America. As Ming Mur-Ray, a Hong-Kong born artist who participated in the CHINA: June 4, 1989 exhibition, indicated that this exhibit was influential and showed the participating Asian artists that they could draw strength from their identity and that they could use it as a theme in their art. (In 2019, the Centre reflects on CHINA: June 4, 1989 in a new blog article and Youtube video.)

|

| CHINA: June 4, 1989 at BlumHelman Warehouse, NYC, October 1989. |

AAAC and Godzilla

In the early ‘90s, major institutions such as the New Museum and the Asia Society in New York City finally recognized the cultural movement in Asian American communities. When they organized exhibitions under the name of “art of identity”, they adopted the issues of the movement as their major theme or part of it. Other groups arose insisting on the recognition of the complexities and delicacies of the Asian American diaspora. One hundred to two hundred Asian American artists gathered in the early '90s, and an artistic network, known as Godzilla (1974), began holding monthly meetings to discuss identity and other related concerns.

Godzilla’s major leading members including, Margo Machida, Carol Sun, Yong Soon Min and Bing Lee were employees or Artists in Residence who made a lot of contribution to the development of the Asian American Arts Centre. The Centre’s effort to establish a place for Asian American artists and their work had played a tremendously important role in the emergence of Godzilla. AAAC had never stopped helping exert pressure on mainstream institutions to change and make the American public aware of cultural developments in Asian American communities. Unfortunately, the Asian American Arts Centre was denied proper credit by the group. Recognition between these organizations was a power struggle that lasted almost for a decade.

|

| At AAAC's Eye to Eye panel. Robert Lee with panelists, Margo Machida (leading member of Godzilla), Lucy Lippard, and Kit Yin Snyder. |

It was difficult to organize the arts community politically due to the lack of a unifying vision that encompassed all peoples. The story of ethnicity in the arts was easily labeled as ethnic separatism and was used as an excuse to downplay its validity as serious contemporary art. Funds were cut and supporters burned out or took other avenues. It began to be time for an alternative vision to replace the idea of art of identity as a sole focus.

If Godzilla and the Asian American Arts Centre had collaborated under an umbrella of one organization and been conscious of leaving their legacies to their post generations, the Asian American Art community could have been much more powerful and generated a stronger impact in the cultural field of the United States. Such a chance will come again to the Asian American community in the near future. The lesson between Godzilla and the Asian American Arts Centre would make their next generation vigilant and alert of their opportunities for forming a solid cultural unit of Asian American Art in the United States and contributing to our better world.

Lee recollects about this long period of retrenchment as follows:

We continued to plug away and do what we knew was right. We understood what had made it so necessary to us to focus purely on identity for so long. How to expand that vision and yet preserve our integrity? We were determined to preserve our community ethics and make frugality a value instrumental in effectively and persistently making Asian American art a permanent if microcosmic fixture on the fringe of the City…Without critical mass, and shedding the conventional ideas of what it means to make it in New York, we sought to amass a history, and a track record of the presence of Asian American art for later generations to build on.

Despite the inevitable struggles for funding, the exhibitions at the AAAC proceeded with boldness, freshness and faith. Maximizing available resources, the Centre never stopped putting together two to four person exhibitions that served as visual conversations around unifying themes.

Important Exhibitions in the ‘90s

|

| Mel Chin, The Opera of Silence, 1988, sculpture. |

The important exhibitions at this time were Passion and Compassion (1996); Three Generations: Towards an Asian American Art History (1997); Inside One (1998); the Day and Night Transparent AAAC 8th Annual (1998); 7lb 9oz: The Reintegration of Tradition into Contemporary Art (1999); and Power Print (2001).

7lb 9oz:The Reintegration of Tradition into Contemporary Art reflected AAAC’s renewed assurance and different perspective. In the exhibition brochure, Lee wrote:

The artists in this exhibition... are for the most part young artists representing three different approaches, with Hisako Hibi representing artists of an earlier generation who took a similar direction. Although what all these artists have in common is Asia as their point of departure, Yeong Gill Kim, Chee Wang Ng, Osami Tanaka and Hisako Hibi, all can be regarded as artists who have resolved what for some artists of diversity in the United States is the conundrum of identity, by a renewed confidence in the vitality of their Asian traditions. The unbridgeable gap of two seemingly irreconcilable cultures is spanned by centering in the roots of one’s historical origins.

|

| Chee Wang Ng, Four Seasons of Brilliance, 1998, 48x48, digital c-print. Included in 7lb 9oz show. |

According to Lee, they assert the Asian presence of difference. Ethnicity is neither conservative, closed, or traditional; it is dynamically changing in the contemporary world and capable of creating new forms:

These artists do not give themselves up to mass perceptions. They keep their distinctiveness. The motives for contemporary art now come from other traditions, other contexts, and their needs, what propels them are different from Western domestic fervors. These artists demonstrate that contemporary art in America need not be founded on the historical experience of the West… [They] assume the responsibility of a re-envisioned, diverse center. Rather than concentrate on the ironies of appearance and identity, Ng, Kim, Hibi and Tanaka have chosen to express the stability and coherence attainable by choosing an inner way of seeing oneself.

Lee concludes by saying that this is a notion at the heart of every religion, at its primordial mystical core:

The role of silence or, it could be termed, the work of silence in the public arena, is part of a re-envisioned center. (Referred to here is 1996 when Senator Bill Bradley ran for president suggested three sectors of American life, I suggested a forth sector or center, as seen in the exhibition brochure.) A value for diverse people to recognize is the process of this silence. Silence is not the best term to use, particularly for some diverse groups, however, it points to what cultures share in their spirituality without raising their separate characteristics. What has been used to describe American life may have omitted its dependence on this spiritual silence. (Senator Bradley’s three sectors – marketplace, deliberative government, & civic cooperation - did not include a forth sector for spirituality or silence. Art and culture may be seen as impractical but clearly they are the air, the foundation for everything. Our nation has yet to put the work into reconciling cultural differences). Incremental steps toward this in America are not without its ethnic dimensions. This is where a re-envisioned center begins.

Art critic of the NYT, Holland Cutter, noticed AAAC’s confidence and renewed stability of direction. Cutter emphasized in his review that Lee had based his exhibition title, 7lb 9oz:The Reintegration of Tradition into Contemporary Art, on the weight of a newborn baby, a symbol of the rebirth and continuation of Asian traditions in art produced outside of Asia itself. It was the first coverage of the organization’s exhibition by the newspaper and since then, its exhibitions have continued to be reviewed.

|

| Gallery Crowd at 7lb 9oz reception, March, 1999. |

The windfall of a group of young artists, whose refreshing creative ideas and sensitivities followed this significant breakthrough, awakened Lee’s colorful and radiant sensibility, which had been in hibernation for a long period of time. Works created ranged from conceptual video exploring ideas such as the inside and the outside, death and life, and examining social constructs, to multi-media installations reclaiming both ordinary and discarded industrial materials such as cardboard boxes. The subjects and the mediums they dealt with were abundant. These artists proved that they didn’t have to depend on their Asian identity to create their works. As Holland Cutter said, "there’s nothing necessarily ‘Asian’ about their works."

The dilemma of difference, however, still remained for the Centre as long as powerful elements in America refused to hear other modalities, insisting on a national identity and a hierarchy that does not give credence to multiculturalism as an important if not defining description of the US. Lee believes in the absolute necessity of a voice from those who live on the fringe and know well what it means to be neutralized and manipulated.

In light of this continuing struggle, Lee now proposes a different American ethos. It is an awareness-of-self in the context of a cultural past. For once one accepts oneself as such, an individual of color has the basis to accept and embrace other individuals and cultures. The multiple perspectives that now compose the American landscape and the global context can be accepted and recognized as a non-hierarchical basis for dialogue and cultural development. Given this perspective, the phrase, 'culturally specific organizations' is a misnomer since for in such organizations, specific cultural roots serve as points of departure to see and embrace the whole.

|

AAAC's Farewell to 26 Bowery Party held Sunday, October 25, 2009.

From left, Zhang Hongtu, Eleanor Yung, and Robert Lee. |

Conclusion

The Asian American Arts Centre has successfully matured, maintaining a symbiotic collaboration with its ethnic community and becoming a role model of community cultural organization. Located in Chinatown, it has been a focal point for cultural and artistic activities of both community members and artists. With long years and difficult stages of passing through of its development, the Centre’s perspective and management skills have matured and refined to the extent that its exhibitions are often evaluated parallel to quality exhibitions of major mainstream organizations. Thus, expanding the accepted definition of a community arts organization.

Even though our globalized economy and politics require us to recognize and accept cultural diversity and the differences of our world, White supremacy still prevails. The orthodox cultural and racial standard of White America runs on cultural oppression.

Color consciousness is the critical effort to open the mind and heart to acknowledge differences in cultures, treatment, privileges, and experiences. Cultural critics in the mainstream academic field have labored long and hard to educate the public on how color and physical disability have unfairly influenced life opportunities. Considering its long history of dealing with the issue of cultural difference, experiencing all the obstacles of being neglected and struggling as well as ultimately regaining its dignity and vitality, it is not hard to believe the Asian American Arts Centre will continue to add dimension to this movement.

Ideally, when the cultural and political policy of the mainstream critical field and the mission of community cultural organizations go hand in hand, the community groups will then have a closer connection and valid role within mainstream culture. However, this is not the reality. The government agency the AAAC depends on for grants now believes that the Centre can no longer be considered eligible as a local community organization due to the attention the Centre received from major news media.

It is time, however, to redefine the role of ethnic community organizations. The Asian American Arts Centre needs to exist and be supported as a community based arts organization. Their longstanding role of educating and supporting their ethnic community needs to be generously expanded to include their mediating and negotiating role between the community and the mainstream. Their purpose is not complete until the mainstream society reflects the reality of this county’s makeup. The Centre should be encouraged to work towards harmony, continuously creating a chain of vibrantly multi-cultural products filled with excitement, empowerment, and communication.

|

| Sculptor, Toshio Sasaki at the 1989, Uptown/Downtown opening reception. |

|

| DETAINED, Spring 2006. An Arab American & Asian American exhibition aimed to bring two communities together around issues of race, exclusion, and spirituality. Chaplain James Yee (center), born and raised in New Jersey, graduate of West Point, chose to convert to Islam after serving in the US Army during the Gulf War. Later he was secretly arrested while serving at Camp Delta in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, on allegations of espionage. Yee was detained for 76 days before all criminal charges were dropped. Participating artists: Wafaa Bilal, Chitra Ganesh, Mariam Ghani, Dorothy Imagire, Pia Lindman, Trong Nguyen, Line Pallotta, Jenny Polak, Dread Scott, Rene Yung, and Visible Collective (VC's photographs are featured in this image). |

.png)